Liberalism as a Stepping Stone for Women

By María Saavedra-Chacón

Those of us who take on the task of demonstrating that the ideas of liberty offer the best tools for the progress and happiness of every individual face the challenge of effectively communicating what we mean by liberty. We often fail to show how versatile our ideas are and their notable presence in the history of many movements and groups that have drifted away from their original philosophies. The case of feminism being claimed by groups that oppose freedom is contradictory because feminism is liberal from its genesis. It aims for equality under the law and the freedom of women to exploit their potential and be creative and happy on their terms. All of which is only possible in a free society.

It is not my intent here to provide a detailed lecture on the anthropogony of feminism because to do so I should be a historian, sociologist or some professional on the study of social phenomena, which I am not. Nonetheless, it is exasperating not only to see some groups stand in the front line of feminism but to witness liberals allowing them to fabricate arguments from feminism and use them against the ideas of freedom, which is absurd. My purpose here is to showcase that the ideas of liberty have served as a stepping stone for women and why our ideas need to be present in the current conversations.

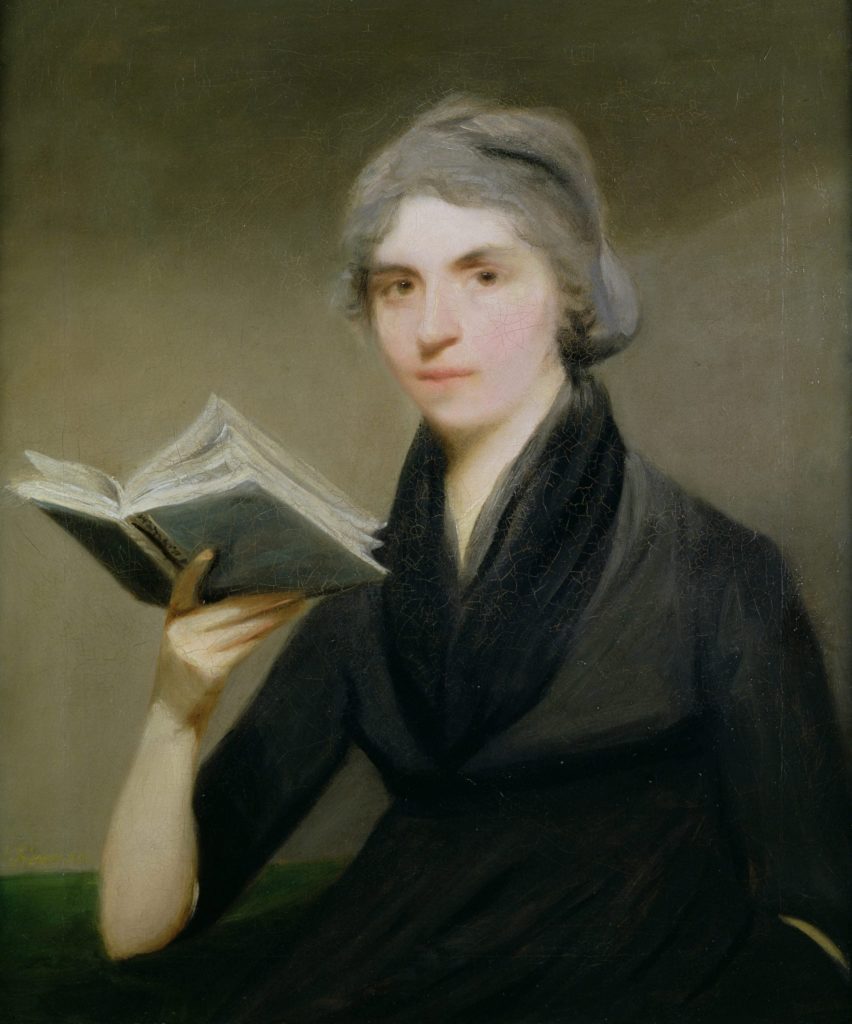

Starting with two important texts, classics that register the achievements of women in their journey towards freedom: Vindication of the Rights of Women (1792) and the Declaration of Sentiments (1848). In the first one, Mary Wollstonecraft describes women and men as morally and rationally equal beings, deserving of the same education. She grants great importance to education as an instrument in the pursuit of happiness. The second one is a signed declaration from the first Womens’ Rights Convention on the United States of America; it alludes to the restraints from the state towards women, which impeded them from getting an education, owning property and exercising suffrage and organizational leadership.

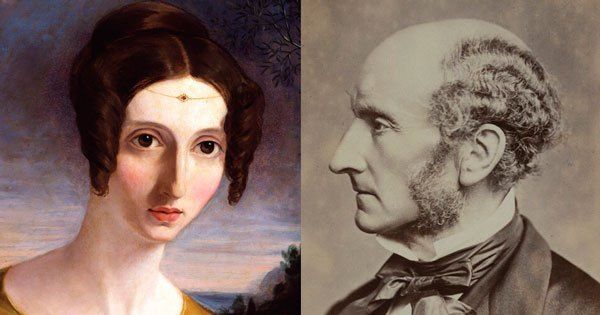

In Enfranchisement of Women (1851), Harriet Taylor-Mill makes a case for the citizenship rights for women and the ineptitude behind the speech that established that women were not apt to exercise the rights that come with citizenship. Taylor-Mill also speaks to the liberation of the labour market, arguing that the only way to know whether women are or aren’t fit for a job position is for them to prove it; meanwhile, their incompetence is a mere assumption. Additionally, the market benefits from competence; job positions are taken by the most qualified individual without distinction of sex.

In The Subjection of Women (1869), John Stuart Mill and Harriet Taylor-Mill share their thoughts on the subordination of women. They provide eloquent arguments on the benefits of female emancipation and their free participation in the labour market and the political space. They write about the absurdness of the deprivation of the right to exercise suffrage, the foolishness of comparing the capacities of men and women based on neuroanatomic differences and how disadvantageous marriage is for women in what should be a marriage of equals.

Women’s happiness has no universal definition because, as individual beings, they have individual wishes and dreams.

The Feminine Mystique (1963), a book in which Betty Friedan exposes the results from her study on college students, reveals the dissatisfaction that governed women’s lives, even if they were able to exercise some of their fundamental rights. This StateState of discomfort that had no apparent source is baptized as the problem that has no name. The subjects feel that their lives stories are being written by the invisible hand of social and cultural expectations for a woman. When reading Friedan’s, my mind is filled with the thought of the profound desire women had to be free to find happiness and to define what that means for them individually. Friedan recognizes that women’s happiness has no universal definition because, as individual beings, they have individual wishes and dreams.

Today, feminist literature is as plenty as the streams in which feminist philosophy has diversified (divided). On liberal feminism, María Blanco, in her book, Unmasked Aphrodite (2017), makes a historical revision of feminism and proceeds to present her personal opinions on topics concerning feminism today from a liberal perspective, while recognizing opposite spheres of thought and without pretending to represent a mass of women of any ideology, for every woman is different. She approaches hard conversations in the liberal space such as abortion, wage gap and discrimination. It is refreshing and interesting to read about the prior topics from her perspective of the world, proving the importance of people from different backgrounds in these conversations and opposing the polarization of speech.

The ideas of liberty have always been and will continue to be the best to stand for the liberty of women and every individual. The pioneers of feminism have found shelter, support and alliance in these ideas. There is not one congruent libertarian that opposes womens’ freedom or anyone’s. We don’t hide behind seductive speech, for our premise is simple.

Every woman is free to: pursue happiness and define what it means for her, participate in every matter and space she wishes, compete in the market and develop her potential.

This piece was originally posted on the Students For Liberty blog.

María Saavedra-Chacón is a college student at Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Honduras double-majoring in Psychology and Nutrition. She currently holds the position of Chief of Staff at Adrianople Group and promotes liberty from her role as Local Coordinator at Students for Liberty and as a member of the Ladies of Liberty Alliance-Honduras. In her free time, she enjoys reading, cooking, exercising, and spending time with family and friends.